We’re on the road again, finally nearing the end of our three day crossing of Brazil from near Salvador in the north east to the Pantanal in the south west. Brazil is huge – so far we’ve done an 18 hour journey and a 16 hour one. Today’s is a mere six, taking us to the middle of the wildlife wonderland of the Pantanal.

It seems like you could paint the countryside here in three bold brush strokes – a sweeping, solid soft blue for the sky, a wave of bright green for the crops, and then a flick of deep, ferrous red, splattering lots of small dots for the earth. Ok, perhaps the last isn’t technically a brushstroke (I’m no artist), but it does fit the landscape, where the bright soil is exhibited through thousands of termite hills studding the vegetation, each one a tower of dirt a metre high and in places the hills only a few metres apart. That’s a lot of ants!

The fields of the Brazillian interior are fittingly vast, the intensive farming here making those bright green crops stretch over the hills and to the horizon without anything of substance to break them up. Every now and then, there’s a whirling cloud of dust rising into the air like smoke from a bonfire, the trail left behind from a tractor heading out to work.

We broke our journey for a day in Brasilia, the capital since it was created in 1960. I say created because the place is very much an artificial construct, conceived by urban planners and visionaries of Brazil’s rural regeneration, and bizarrely, a 19th century Italian priest.

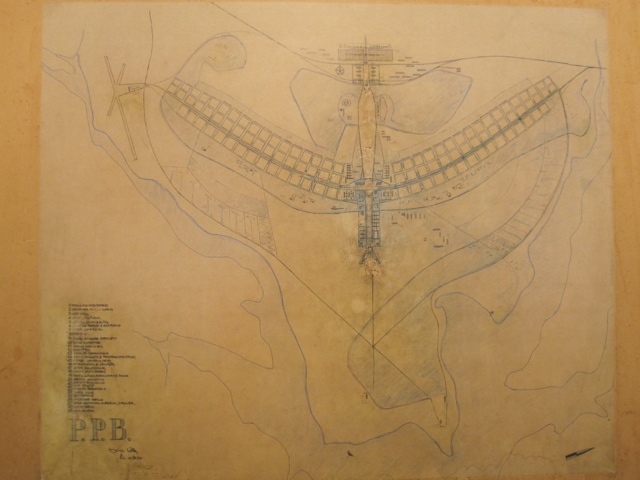

The story goes that the Turin priest Dom Bosco prophesied that a new civilisation would emerge somewhere between the 15th and 20th parallels, roughly in the centre of Brasil. Years later, in 1955, this was seized upon by President Kubitschek, who used the idea of a new capital to focus Brazillian’s dreams of their country’s emerging power and huge natural wealth, as well as to kick-start economic development of the vast interior plains. Incredibly (and perhaps even more potently as a symbol of the country’s strength), the city was built (mainly) from scratch in just 3 years. As a clean slate, it represents a sixties vision of urban utopia – open skies, outstretched and ordered blocks of grey apartments, six lane highways, lots and lots of concrete and, perhaps a little more surprisingly, a city designed to be the shape of an aeroplane. The ‘pilot plan’ called for the wings to be filled with residential areas, the fuselage to hold key public buildings and rows after row of government ministries, and the cockpit to house congress, the judiciary and the presidential palace. It’s certainly organised, if a bit of a nightmare to negotiate on foot!

The cathedral (it was closed, so no amazing stained glass this time). Note the innovative bell tower on the right!

I was actually a bit more impressed than I thought I was going to be. Strict planning laws mean that there are huge amounts of open space – you can almost see the whole sky walking down the avenue running down the middle of the ‘plane’; it feels cool and breezy with the air flowing in over a huge artificial lagoon, and some of the architecture – especially the national museum, library and congress – is pretty elegant, if somewhat monolithic. We dropped in to Congress and went on a short guides tour; politicians are the same the world over – each chamber was pretty much deserted except for a lone representative giving a speech for the benefit of TV and some bored looking cameramen.

A TV reporter inside the lobby in Congress. You can just about see he's wearing jeans with a suit jacket for the headshot on camera!

Even if opinions are still divided on the success of Brasilia, it’s clear that Brasil has succeeded in what it represented – that this is very much a country on the way up. I gather the news back home has been peppered with reports of Brasil’s economy overtaking that of the UK; from here it isn’t hard to see why.

A huge Brazillian flag, 274 square metres in size, with a massive flagpole welded from one from each state

Simon