The view over the city from the tower

Having spent an exciting few days in the busy Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), we’re now on a sleeper train heading north for the calmer town of Hoi An.

It’s consistently an interesting experience arriving into a new country and needing to recalibrate. Obviously there’s the language and currency, but also the street price of everyday items, since in a world with few displayed fixed prices it’s easy to get ripped off. There’s also the question of transport, a somewhat integral part of ‘travelling’! In India, we quickly fell into the routine of rickshaws and trains; here we’re told that for travel in town it’s taxis (ok, but perhaps a bit pricy for us), being a passenger on a motorcycle (err, does that work for two?!), or cyclos, essentially a glorified cot stuck on the front of a pedal bike (which again are designed for solo travelling). We’ll keep you posted on how we get on with these – or whether our feet pay the price for our lack of a sense of adventure!

Fortunately, the trains seem to be pretty good; we’re in one of the less luxurious 6 berth ‘hard sleepers’, which is clean, and even has a door – a feature absent from the Indian trains we loved so much. The only bad thing so far seems to be the lack of boiling water. We brought noodles to, err, instantiate (well, they are instant, right?), but so far – and I’m on the fourth attempt now – there’s only been cold water from the boiler. I think five will be our lucky number though!

Not what we expecting to find for sale at the airport!

Arriving from India, exhausted after two flights and a nine hour stopover on the hard floor of Kuala Lumpur airport, HCMC was a bit of a shock. It’s like being in Europe! There’s French architecture and boulevards! There are even pavements! Oh, and in a less European feel, there are lots and lots of motorbikes, many on these very pavements!

The rise of the motorbike is a pretty good proxy for the city’s economic rise, itself largely as a result of the tourism the country has experienced since it opened borders to the west in 1989. According to a guide the other day, ten years ago there were 200,000 bikes on the streets, for the 8 million inhabitants. Now there are 4 million, one for every two people. And it really feels like it – a swarm of roaring, screeching, honking two-wheeled insects that seem to get everywhere.

Motorbikes everywhere!

It’s hard enough trying to cross the road when there are no lights and just a continual mutating mass of metal and rubber pouring towards you. The trick is just to keep walking forward slowly, dodging only the cars and buses; the bikes will dodge you. However, early on, we made the mistake of trying to cross the city on foot at rush hour – never again! The added complication here is that the bikes also use the pavements as spillover lanes, in their thousands. It’s so common for bikes to use the pavement that the curbs are almost all ramps, for ease of access. It’s the easy cure-all! One-way street getting in the way? Use the pavement! Traffic jam on the tarmac? Stand aside, pedestrians! No right turn? You guessed it! The net effect of the chaos is that every time you cross

a road, you need to look both ways, simultaneously – to monitor both the regular traffic, the bikes on the periphery of the street heading in the other direction, and then the pavement traffic, which can come from anywhere – including the sneaky side-alleys that sub-divide each residential block. At one point on our journey home, we faced a comical (in retrospect, anyway) decision – to wade through the dense stream of bikes coming against us on the main pavement, or to take advantage of some building work that was going on and had cleared some space in which to walk – but doing so meant walking under a guy balanced on a bamboo ladder using a power drill on the cladding of the building above. Having used our best risk assessment skills, we chose the builder’s route, although there was a moment of total panic for me when I thought I heard the sound of breaking tiles from on high!

Laura and Sarah on our evening out

Happily, we’ve also been able to meet up with my friend from work Sarah Mann, who’s at the end of a Gap Adventures tour of the country. There’s something fantastically reassuring about seeing a familiar face, and it was great to catch up over food and drinks on a couple of evenings. Big thanks to her for bringing a couple of much-needed supplies out from the UK. Unfortunately we left her yesterday to carry on with our day jobs – for her, risk management; for us, adventure – or perhaps that’s risk taking, if you want to look at it that way!

Wandering around the sights of HCMC, there are continual reminders of the war and its devastating impact on the country. It’s a little hard to separate the propaganda from reality – for example in how unified the country really is under the red flag. The communist government (who won the war and reunified the country) renamed the city after the communist party’s founder, Ho Chi Minh – but locals still prefer to use the former name, Saigon. We’re told there’s a strong north/south divide too – with the south having modernised and being the major source of investment and trade, while the north has more of the country’s ideological and cultural base.

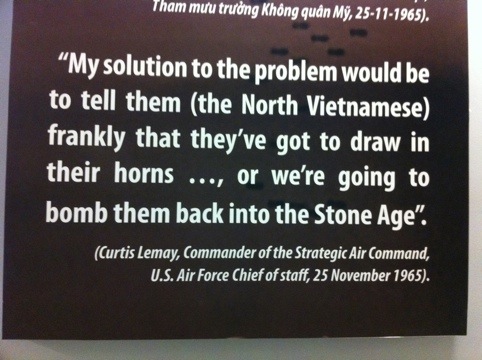

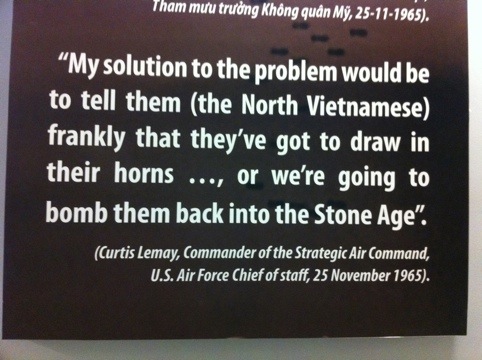

Shock and awe?

Simon in the Cu Chi tunnels

The narrative of war presented is one of communist cunning in the face of massive American military supremacy, exemplified by the tunnels at Cu Chi, just north of the city. Originally for storage but connected up in the war, locals constructed some 240km of tunnels in the clay beneath the forest, some three stories deep, with hidden entrances, and various traps to ensnare American troops. With many underground for long periods of time, there were bunkers to live in, including ingenious methods to disperse smoke from cooking fires so it rose far from the original source. We got a chance to crawl 40m through a tunnel widened for westerners (still very cramped!), and you can see Laura modelling a tiny hidden tunnel entrance. Sadly, this conquest of brain verses brawn just meant the American military machine brought in the policy of total destruction of the landscape to rout the Viet Cong, through B52 carpet bombing, and the infamous Agent Orange as a defoliant.

A trap for American Soldiers

We also took in the very seventies Reunification Palace, still used for state events, and site of the defining image of the end of the war, with the two tanks that broke through the gates still present in the grounds. There was also a chance to see amazing views over the city from a newly opened skyscraper – photo at the top.

Laura in the entrance to

the secret tunnel

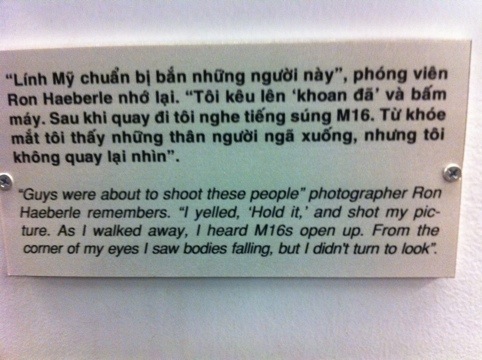

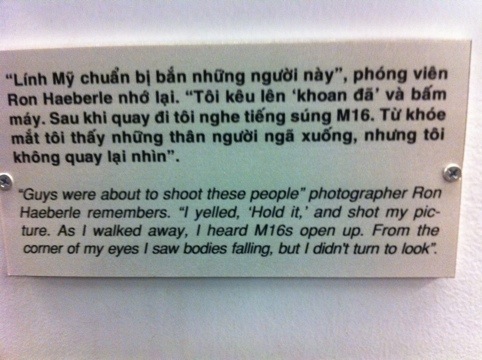

It took us two visits to get round the distressing exhibitions of the war remnants museum, which show the chilling destruction wrought by twenty years of war in photographs. These include a touching memorial to photojournalists who died exposing the truth of the conflict, with many of their final photos on display. It’s hard not to be disgusted by the barbarity of war and lack of respect for human life, especially of civilians. The photo caption pictured below from a western photographer really speaks for itself. Apparently there have now been more suicides of American troops suffering post-traumatic stress than there were American deaths during the conflict itself.

One last thing – Agent Orange, or to give them them their true name, dioxins. My photojournalist friend Michael Carroll has exhibited some incredible work on the horrifying effect these poisons had on the people – of the war, but also future generations, such is the nature of chemical warfare. However shocking the imagery is (and it is), I don’t think I’d appreciated the scale of the problem. Let me give you a few numbers. It’s believed that 3 to 4 million Vietnamese have suffered illness (or death) as a result of the chemicals sprayed, and tens of thousands of troops on the side doing the spraying – American, but also other asian allies – were affected too. These chemicals were made by large western firms who still thrive today, names like Monsanto and Dow Chemical. At the end of the exhibition were some newspaper articles, including one from August 2010, entitled “At least it’s a start”, recognising the $12 million committed by the US Aid programme to start clearing up the chemical mess they left behind in dioxins at their Vietnamese military bases. I think this was generally praised as a positive move in the international press at the time, but you really have to see it in context. The same bill announced more funding for the US soldiers who were victims of dioxins, this to the tune of $13 billion. Yes, that’s million vs billion. For the sake of the millions of affected Vietnamese who have to live amid it every day, I hope it is just a start.

Simon

The hand of friendship?

PS. We finally worked out how to do captions. Hope you enjoy them!